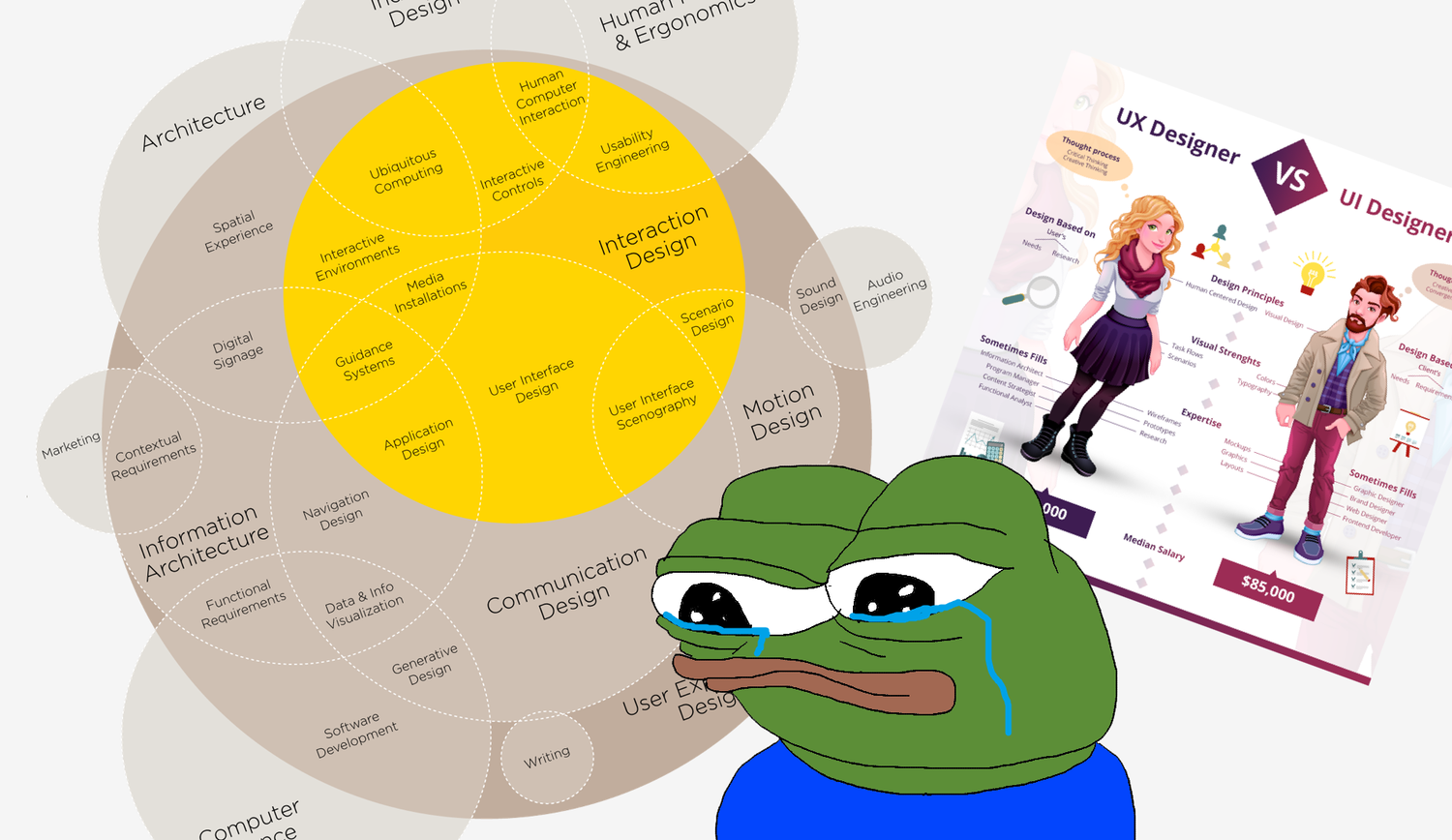

Let me ask you: what do you do? What title do you put on the resume and portfolio? Why these words? I invite you to an exploration of how design titles and design directions are (not) connected with the real world. So, let’s take a look at the current state of things. I guess you’ve seen different attempts to distinguish between UX and UI, UX and CX, user experience and product design, and so on. And you might have seen schemes about designer types like UI and UX designer, UX and product designer, etc. These adorable circle diagrams have got so sophisticated over time.

If you’ve ever googled such stuff, you probably noticed these schemes give few answers and don’t tell much about design and designers. Something significant is always missing — value. Value for other people. Without value shown, such diagrams only serve a topic for designers’ snobbish chatter at 11 AM at the coffee machine. For the majority of people — people who do not live in the world of pixels, fonts, and canvases — it’s nonsense.

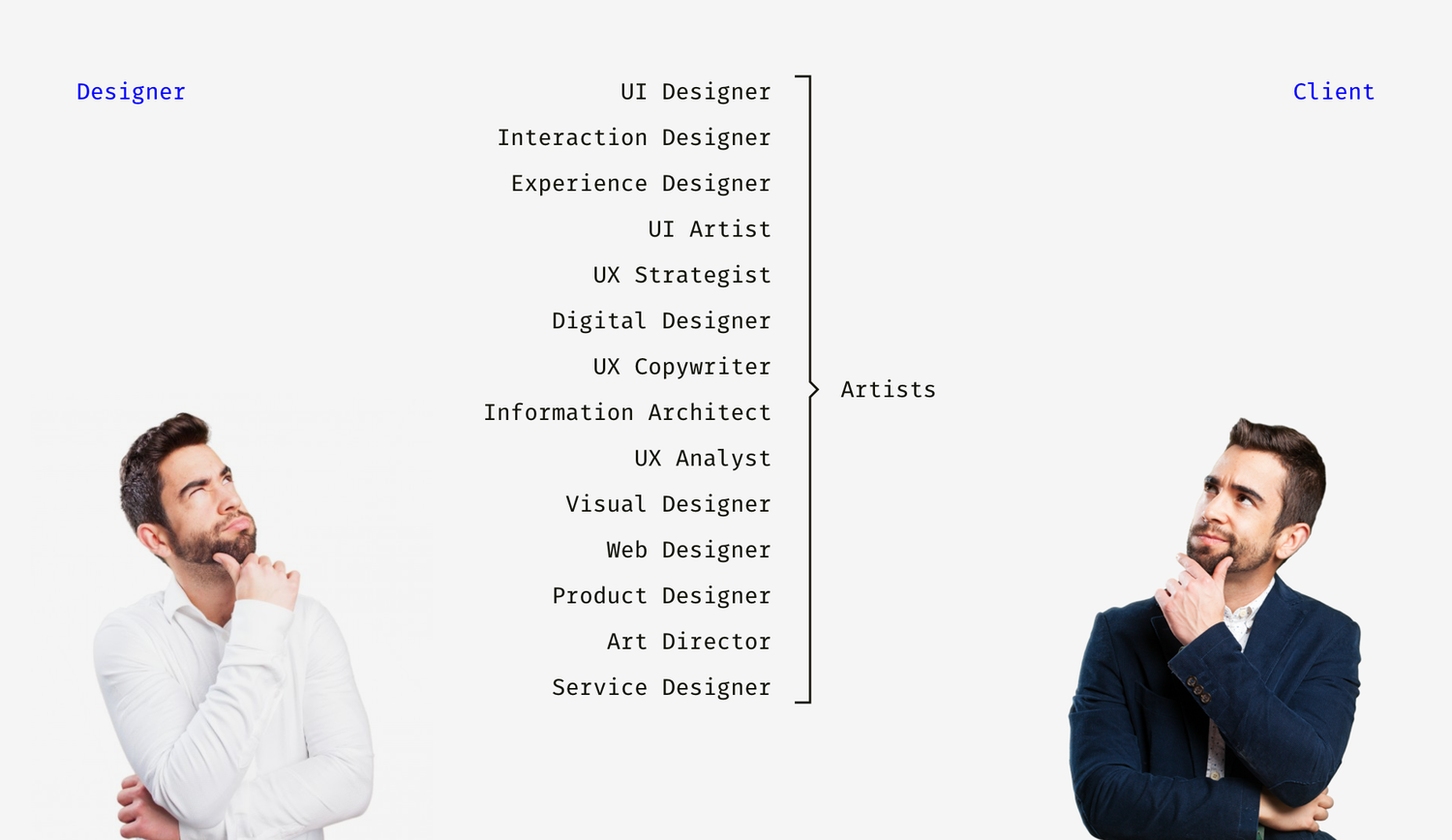

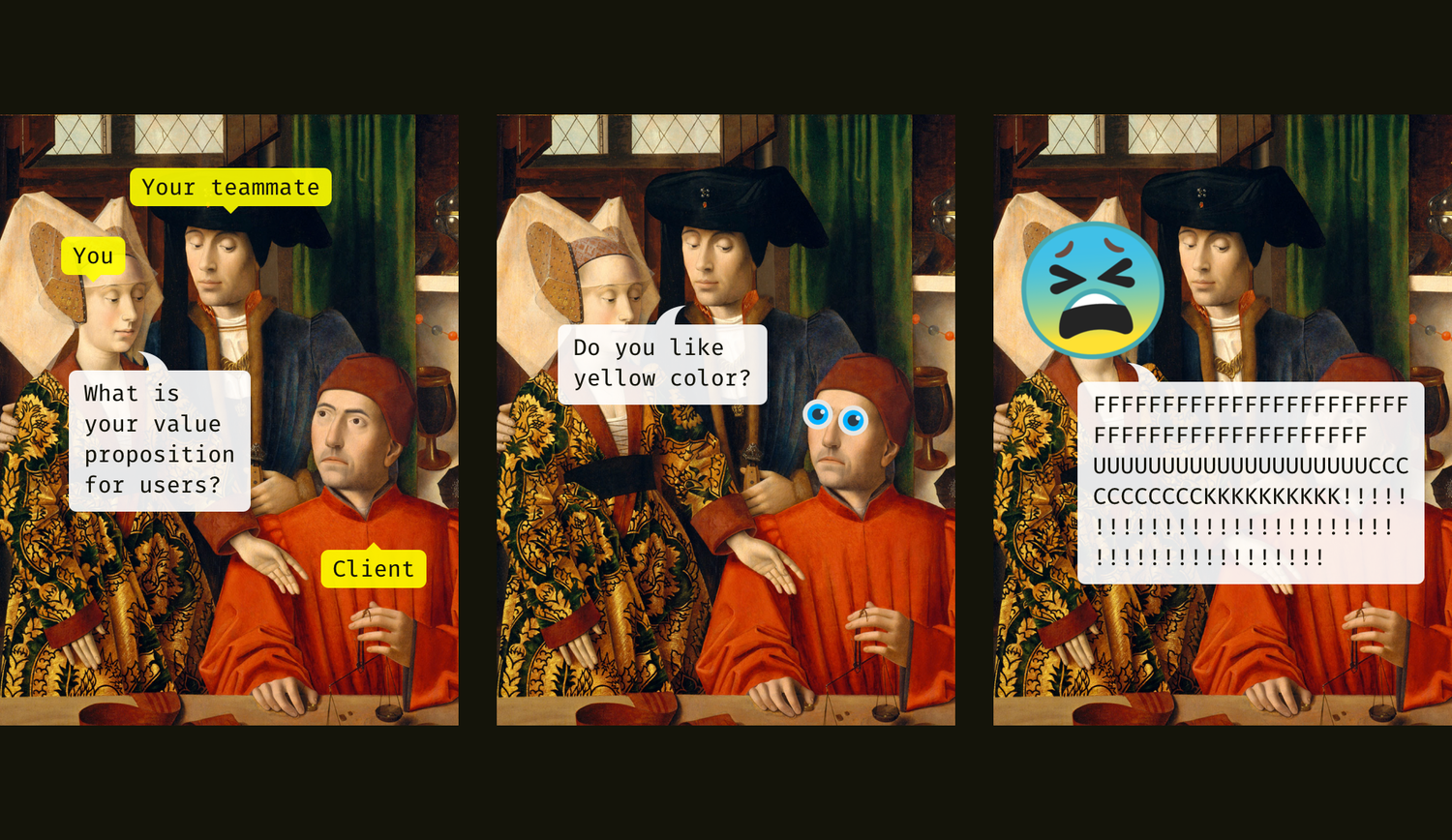

I remember the time when I tried to “enlighten” clients and rolled my eyes at them when they confused terminology. Now I know for sure who created so-called clients from hell — designers from hell. Such as me several years ago. We are in the trapping pit we’ve dug. Difference between UX, CX, UI, IxD, and other abracadabra doesn’t ring people a bell because it’s theoretical and exists only in the designers’ imagination.

“UX/UI designer” sounds as awkward as “vegetable/carrot salad” or “vehicle/bus driver”.

Furthermore, designers’ abbreviations are the result of bad design. Think about this: can professionals who strive for clarity and simplicity call their jobs so unclearly that they need to explain them? “UX/UI” is the champion of dumbness. What does the slash mean, I wonder? So, you do both or one of them at a time? If these are two essential parts of one thing, why not call it with just one word? If these are different things, why do you do two jobs simultaneously? Moreover, why do two elements of different logical levels stand together? User experience is more general and exists before, after, and even without any interface. Why is the word “user” mentioned twice in this 4-letter acronym? Why is “experience” abbreviated to X, not E?

Even such a popular title as User Experience Designer (UX Designer) is a goofy pleonasm, basically, using more words than needed. It’s similar to saying Quality Assurance Tester, Talent Acquisition Recruiter, or Software Engineering Developer — as if it gives you more importance.

I have a hypothesis that the modern outbreak of creative design types and titles is naive resistance to stereotypes. Maybe we are adding descriptive words and replacing “designer” with “strategist,” “architect,” “analyst,” and “developer” to run away from “make it look sexy.” The latest trend is to call yourself a product designer or product manager. “Product” has become the new “UX” these days. Isn’t it a vicious circle? The word “design” has lost its true meaning, and instead of bringing it back, we annihilate it employing all these evasive words.

All in all, there is no matter what you call yourself and your approach if the result of work lacks tangible value. If a designer draws wireframes, prepares prototypes, conducts workshops, but cannot deliver a solution for a problem, he or she is anything but a designer.

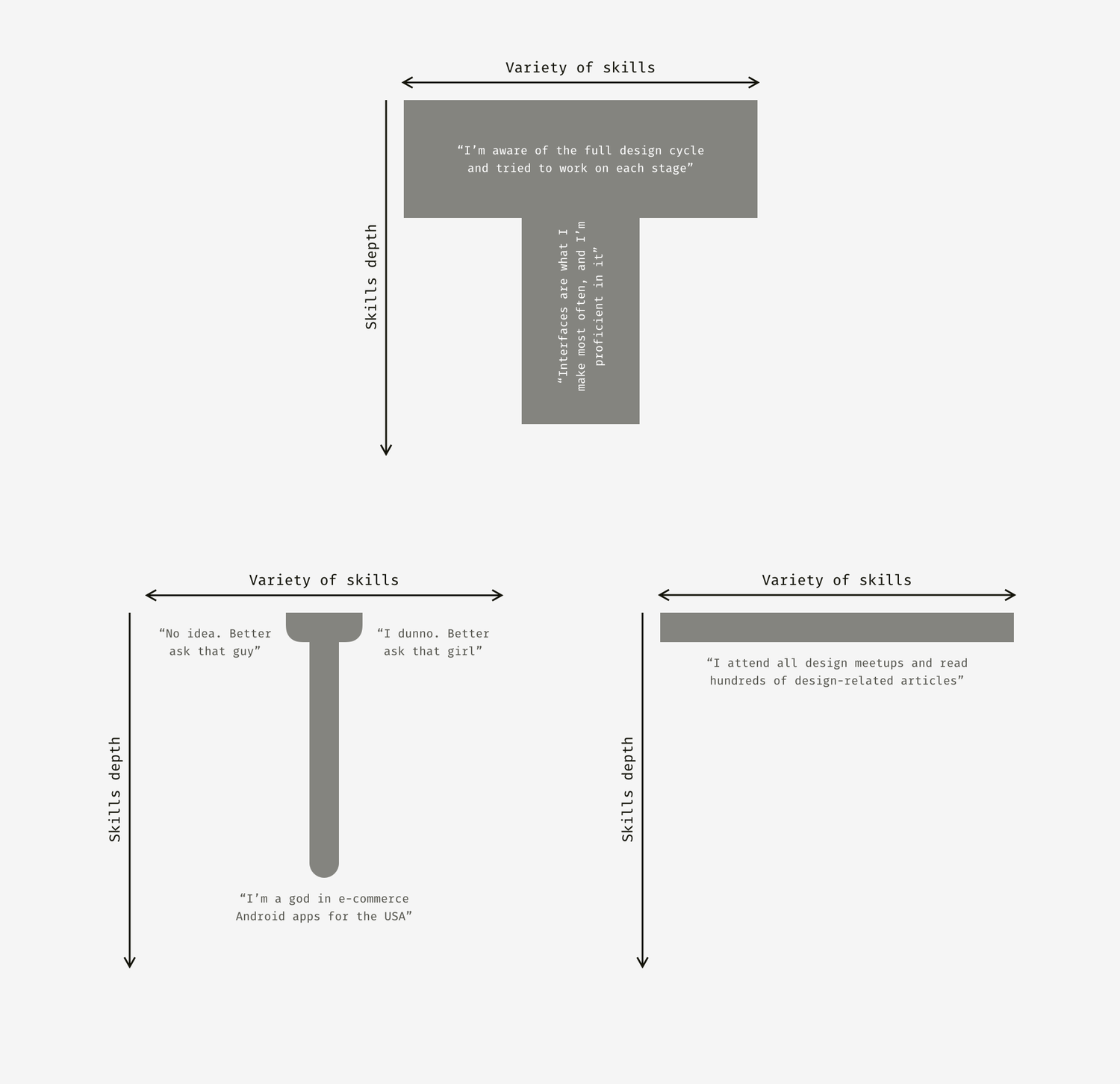

So, what are designers supposed to do, in the first place? Where is the balance between focusing on a narrow area and being in charge of all design activities? Where is the verge between drawing mockups and influencing the world? There is a popular idea that a T-shaped skillset is the best for a designer. It means a designer has a deep competence in some area and decent knowledge in the rest of the design areas.

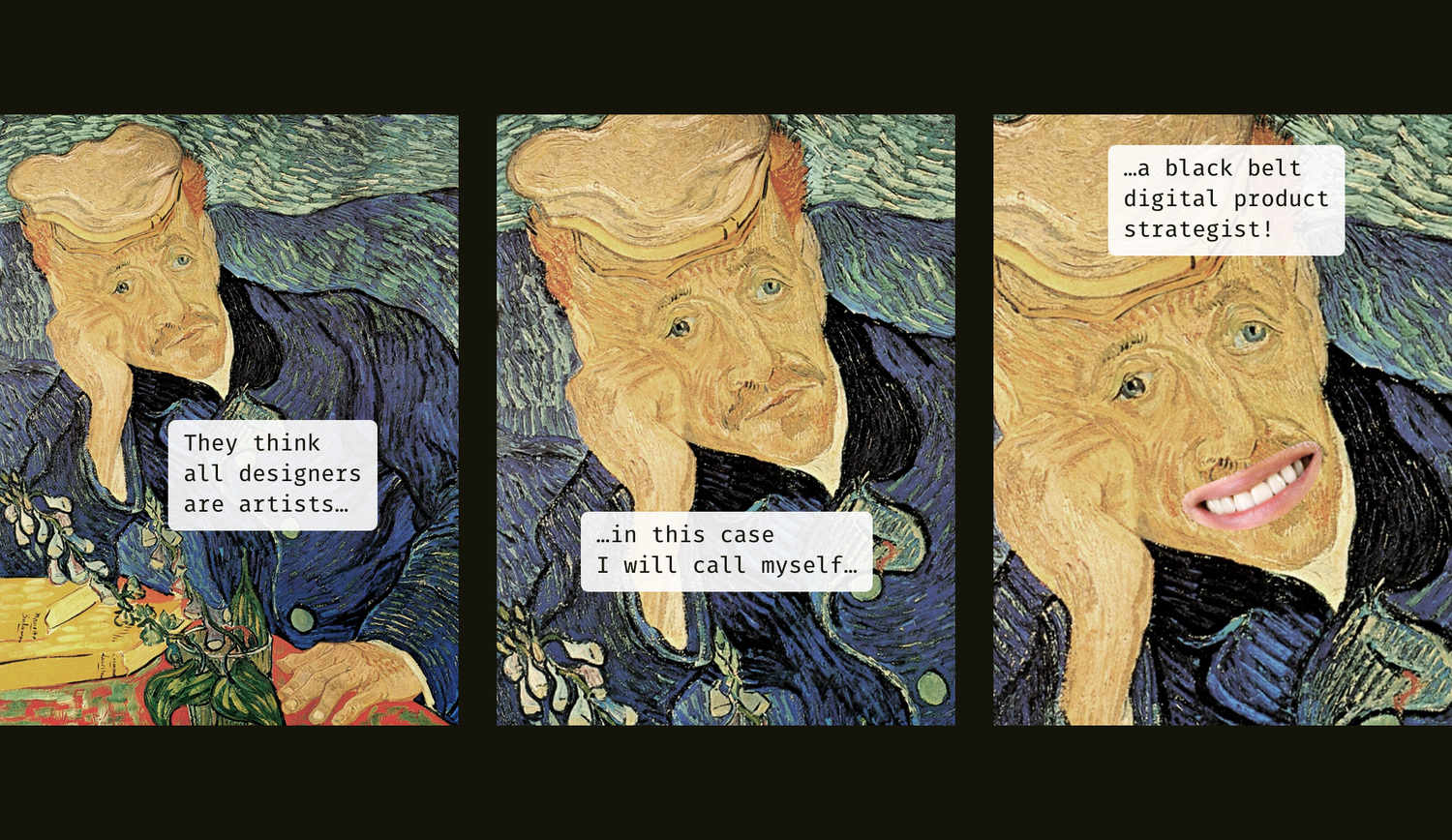

However, we are living in a weird age when the design industry is evolving fast, and people risk to obtain two dangerous skillset types. I call them the “dick-shaped designer” and “em-dash-shaped designer.”

The first one is a specialist who knows only one narrow area, and if anything is beyond it asks to consult the other specialist. Such skills don’t allow to think strategically and keep the core value of what a team does in mind. I often hear, “Oh fuff, I don’t draw icons. I’m a UX designer. I pass my wireframes to a UI guy.” Or, “I pick the color palette. You’d better ask about the business model that girl at the whiteboard.” What’s next? Will there be Blue Button Designers? (Do not confuse with Red Button Designers.) Flat Icon Architects? Customer Journey Map Strategists? Principal Sticky Note Peelers? To feel how grotesque it sounds, try modifying non-design job titles: Steel Hammer Carpenter, Lurssen Yacht Sailor, Asian Flavor Cook, Beretta Gun Soldier, Canon Mark V Photographer.

And since design thinking is a hype nowadays, there is another problem — em-dash-shaped skills. These folks attend dozens of design conferences and courses and know a little bit about everything. It’s not bad; we all used to be novices at some point. What is awkward is when they start to mention all the areas they pretend to know. For instance, UI/UX/Web/Mobile/Desktop Designer or Service/Product/Project Manager.

You may disagree with the thoughts above, “It sounds cool in theory. But these buzzwords are exactly what HRs, recruiters, and potential clients are looking for.” Well, this is right to a certain extent. And what about professional dignity? If it becomes trendy to call our job “Pixel Mover” or “Photoshop Operator,” will we put that on our resumes?

I think large companies have also contributed to unteaching designers to be… designers. This zoo of design types is the result of granular work distribution in big teams. Designers are doing their small parts and gradually unlearn to see the final goal. Throw stones at me, but the end-to-end design process is a must for any designer, although they can specialize in something.

Methods vary for every industry but the core is the same: research, ideation, validation, implementation.

If we call ourselves designers, I believe we should take responsibility for the whole product fate even doing a small portion of work at a time. If icons, wireframes, mockups, icons, or prototypes are neat, but what people get is a disaster, designers haven’t done their work. Let me make myself clear. I don’t promote being a design generalist versus a design specialist. Just pointing out our work is more responsible than we imagine.

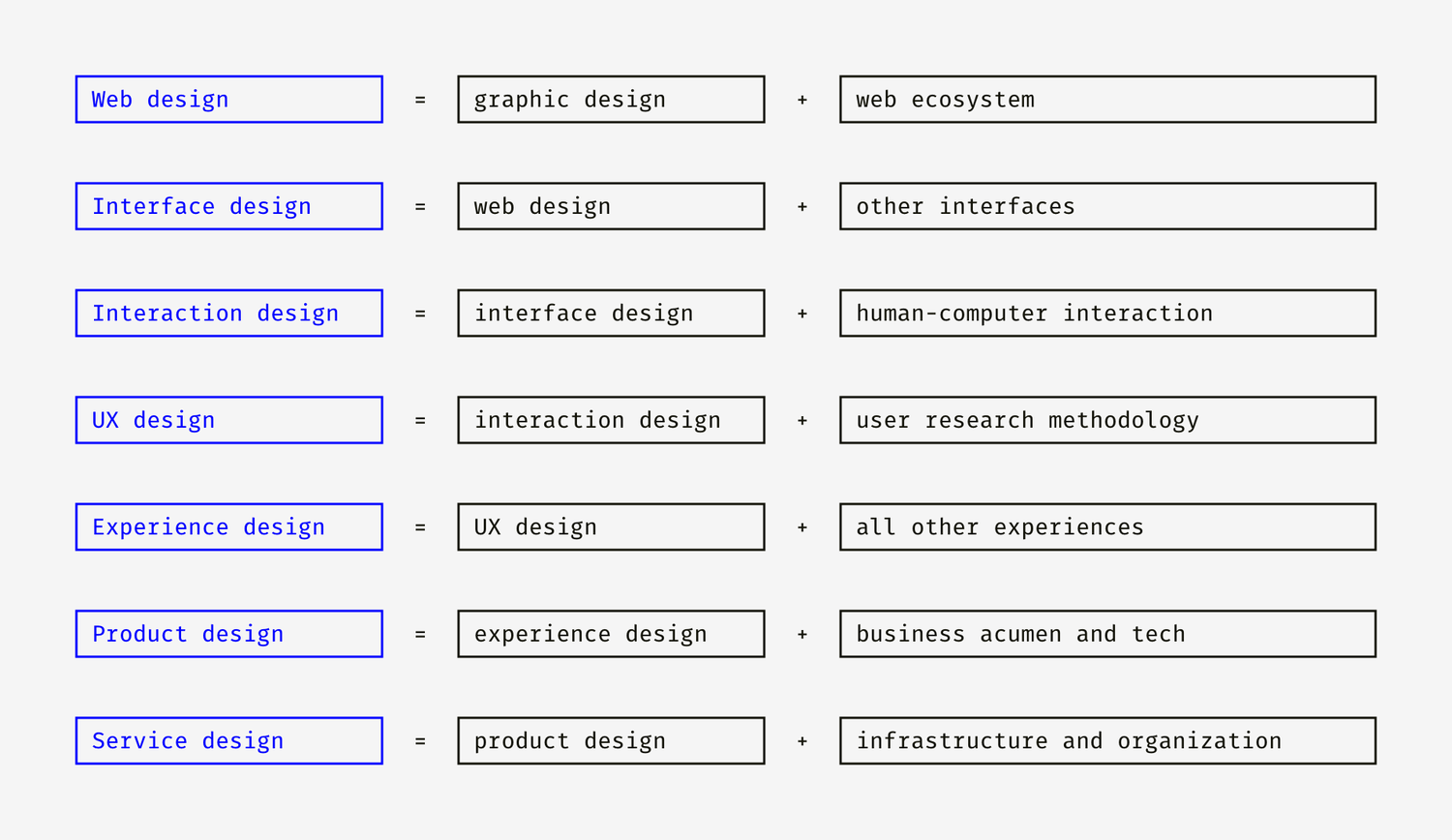

Now we can return to the questions from the beginning of the article. What are we? What are we actually doing? And here is another observation. Designers’ area of responsibility grows each year. Present-day titles more and more reflect how we work because there is not much difference between the principles of designing a mobile interface and a microwave oven. “If you can design a thing, you can design anything,” said Massimo Vignelli. It means the designer’s mindset is more important than tools, and you’ll learn the tools fast if you know what to do next.

We should be able to show the measurable value of what we consider is right. Sometimes designers propose solutions that don’t bring immediate income but, for example, attract loyal customers. Loyalty and the company’s reputation will bring money in the future. The trick here is to show how it’s possible. It’s like playing chess: the more steps ahead you think, the more credibility and trust you again.

Understanding and proving the value of design is one of the basic topics in our profession. Photoshop, Sketch, pixel perfection, customer journey maps, visual language don’t make us designers. The same way a hammer and a saw don’t make someone a carpenter. We are designers when we solve problems and contribute to something valuable.

There will always be people and situations that break the reputation of our profession. A popular meme says, “There will always be someone who can do it cheaper.” Fortunately, there are simple things everyone can do to support the credibility of designers.